The crack of the bat, the pop of the leather, the stare down over player valuations

Baseball has a new spring tradition, in which many perfectly good players find that teams don't want to pay them what they think they are worth

A few years back I wrote a piece about the various problems with North America’s major sports leagues that contained the modest proposal of killing the playoffs.

Amazingly, no one took the advice.

They never would, of course, as noted in the piece in question. Sometimes, columns offer realistic solutions to a problem. Sometimes, they are thought experiments playing the crucial role of filling the news hole that exists between Christmas and New Year’s.

But the arguments for scrapping the playoffs are just as valid in 2024 as they were in 2019. They’ve probably even strengthened.

The point is not that the playoffs themselves are flawed. Playoffs are great. Everyone loves playoffs, right up until your team is facing elimination, at which point the playoffs become basically a two-hour heart attack. Which is still fun in its way.

No, the thing with the playoffs is that they are now so important — and, increasingly, so long — that they have rendered regular seasons largely irrelevant. The NBA is furiously trying to counter this trend with the addition of a play-in tournament at the end of the regular season, a new midseason tournament to give extra meaning to games in November and December, and introducing rules meant to curb the rest nights so often given to star players in recent seasons. The NHL, as is its way, has done nothing. The NFL, and especially Major League Baseball, have gone the other way, adding playoff teams to increase the number of high-demand TV dates even if that means further devaluing the regular season.

And devalue it, it has. Several of baseball’s best teams weren’t around long last October. The 104-win Atlanta Braves, the 101-win Baltimore Orioles and the 100-win Los Angeles Dodgers all crashed out at the Division Series stage of things, knocked out by the 90-win Philadelphia Phillies, the 90-win Texas Rangers and, most embarrassingly, the 84-win Arizona Diamondbacks. The Diamondbacks didn’t exactly storm into the postseason, losing their last three games but getting the third Wild Card spot, which didn’t exist until 2022, anyway.

And so, three teams that played dominant baseball over the course of six months, which is a true test of everything that makes a team good, were dumped out of the playoffs in a best-of-five series that essentially amounts to the flip of a coin. Those are, obviously, the rules. None of the losing teams should claim that this is unfair.The Braves’ incredible lineup went cold, the young Orioles were always going to find their first playoff appearance tricky, and the Dodgers seemed doomed pretty much from the outset, when Clayton Kershaw once again got shelled like only he does in the postseason.

But a few months after the Rangers beat the Diamondbacks in the World Series, and with spring training games underway, it feels as if most of baseball has decided that there’s no point in trying to be great. Slightly-above-average is the new market inefficiency.

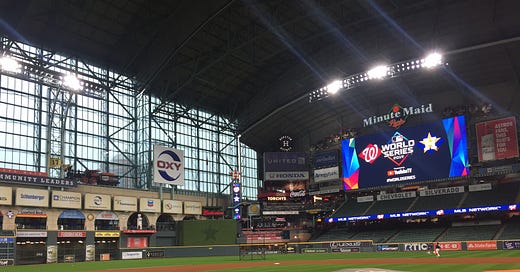

With the obvious exceptions of the Dodgers, who committed the GDP of a lesser island nation to Shohei Ohtani among several big moves; the New York Yankees, who traded for outfielder Juan Soto; and the Houston Astros, who shovelled money at closer Josh Hader, MLB front offices have done a whole bunch of tinkering. The Orioles traded for starting pitcher Corbin Burnes, but that seemed like the least they could do to bolster a young, cheap roster.

And, hey, look at that: the only teams with playoff odds above 80%, per FanGraphs, are the Dodgers (95%), Astros (87%) and Braves (96%). Atlanta has been relatively quiet over the winter, but the Braves were loaded to begin with.

Meanwhile, a comically large batch of unsigned free agents is waiting to be snapped up by any of the other 27 teams that are not strong favourites to make the post-season. These are headlined by the Boras Four Three (Blake Snell, Matt Chapman, Jordan Montgomery), veteran clients of noted hardass Scott Boras who are expected to command giant contracts, but also dozens of merely good players who would normally attract plenty of interest. J.D. Martinez, Adam Duvall, Brandon Belt, Mike Clevinger, Tommy Pham, Whitt Merrifield, and I’ll stop now because you get the point.

(Another Boras client, Cody Bellinger, signed a three-year, US$80-million contract to return to the Chicago Cubs that seemed a lot like a surrender. He can opt out after a year and try again on the open market.)

When it was difficult to make the playoffs these were the kinds of players who were in demand by teams that needed an upgrade or two to become fringe contenders. But with a 12-team playoff field, the distance isn’t far from middling roster to playoff bubble. And as the Diamondbacks proved last year, even a last-gasp playoff team can ride variance luck to the season’s final series.

By those same FanGraphs projections, fully 17 MLB teams — more than half of them — have playoff odds this year between 29% and 67%. Not terrible on the low end, but not enough to feel really confident on the high end, either. And yet none of them appear to be, in the parlance, going for it. In a sport without a hard salary cap, and with all kinds of quality talent available, so many good-but-not-great teams are in wait-and-see mode. (The Toronto Blue Jays are among this group, but we’ll get to them in a coming post.)

Several of those teams have uncertainty with their television revenues, after the collapse of of a company that held regional rights for dozens of pro teams, but while that’s probably a factor it also points to the opportunity for unaffected teams. Wouldn’t now be a good time to go all-in?

The players, it is worth noting, were afraid this would happen. MLB wanted to expand the playoffs to 14 teams, but the players’ union worried that this would reduce the incentive to spend to be competitive.

They agreed two years ago to go instead from 10 teams to 12. And even then, it seems the players had a point.